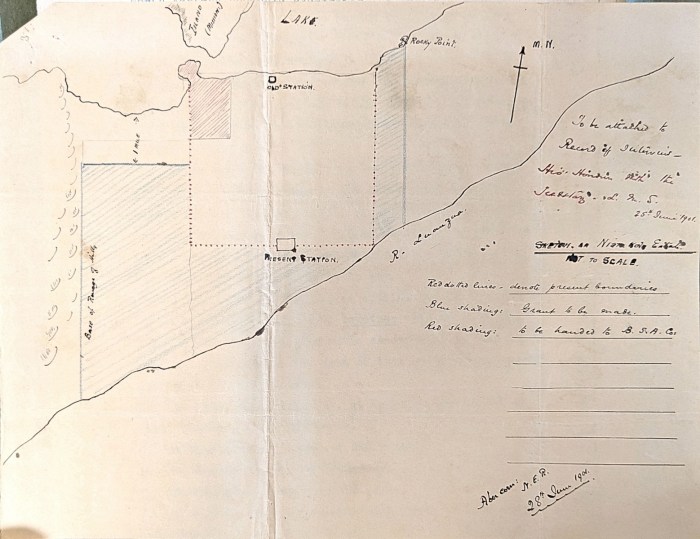

A mea culpa: just two posts ago I talked about how I didn’t really have an explanation for the above map (and an accompanying letter), which was illustrating land that the London Missionary Society was swapping with the British South Africa Company (BSAC) around their Niamkolo station. That post was part of this ongoing series where I put online things I found in the SOAS archives, and this post continues that because if I had scrolled a little bit farther down in my file I would have found the answer. I didn’t fail to do that just to stretch two posts out of it, I was just silly. I had speculated in the previous post that maybe the answer was trains; much more excitingly, it was boats!

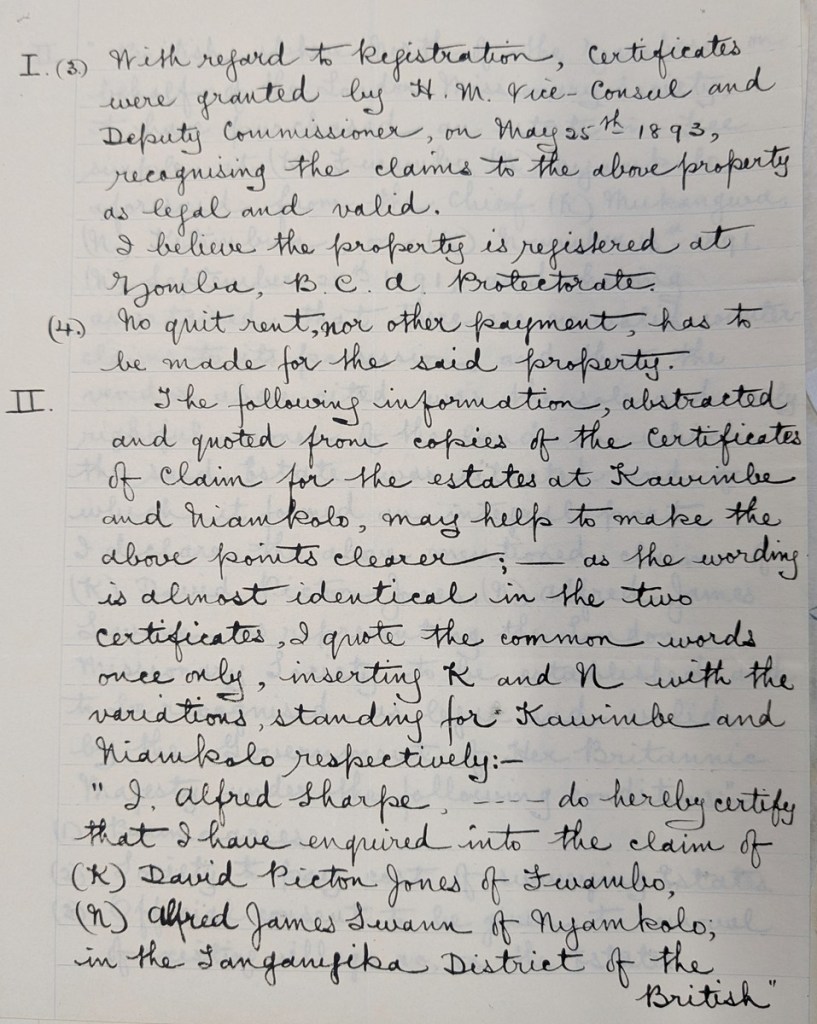

The letter transcribed:

Tanganyika Concessions Co. Abercorn

Dec 4th 1900

Dear Sir,

Mr. Irwin, our Traffic Manager, who is about to put together our steamer “Cecil Rhodes” on the lake, has carefully examined the two sites that I had chosen, namely Niamkolo and Kasakalawe. Mr. Irwin has decided to build his steamer at Kasakalawe because he is in hopes of getting there erected houses and sheds of the Flotilla Company. Also there is a good road to the place and no uncertainty about freehold possession. However, there is no anchorage there and Niamkolo is the only possible place where we could with safety erect our patent slipway, being an ideal anchorage. In the future we shall have to find some good anchorage for the repairing & docking of our steamer & other companies’ steamers. The other Cos will probably gladly avail themselves of our slipway.

I therefore shall ask your Committee to consider whether you would let us have permanently one half square mile at the mouth of the straight opposite the island by the shore, about 2 ½ (or 2) miles from the Mission house, & out of sight of it. A road would be made to it from Abercorn, which would skirt the [?] village at some distance – we should be glad to pay for this land, to give you a site in the new Abercorn, which will be begun next year, and which is absolutely the property of our Company, and to grant you special rates in steamer passage & transport on Tanganyika – the B.S.A. Co. have the right to ground enough in our new town to build there their offices, but they will not encourage anybody to build outside our township, except at very large prices as they wish our Company to succeed. I have no doubt that Mr. Codrington will grant us the 2 square miles that I have applied for at Kasakalawe to make an official port, but we would far prefer to be at Niamkolo, as a better anchorage. If there is a possibility of a mile square being sold to us at Niamkolo, we would let Kasakalawe lapse & make the official port at the former place, but if only half or quarter mile is allowed us we shall only be able to put a few [?] and our slipway there – A half-mile would possibly be ample – a quarter mile is rather cramping.

Kindly let me know the Committee’s views on the subject. I hope that if you consult your Directors at home you will be good enough to forward them a copy of this letter. This would be more direct than if I sent a copy through my Directors to yours.

Believe me, yours faithfully,

M.J. Holland, Lake Tanganyika Concession Co Ltd

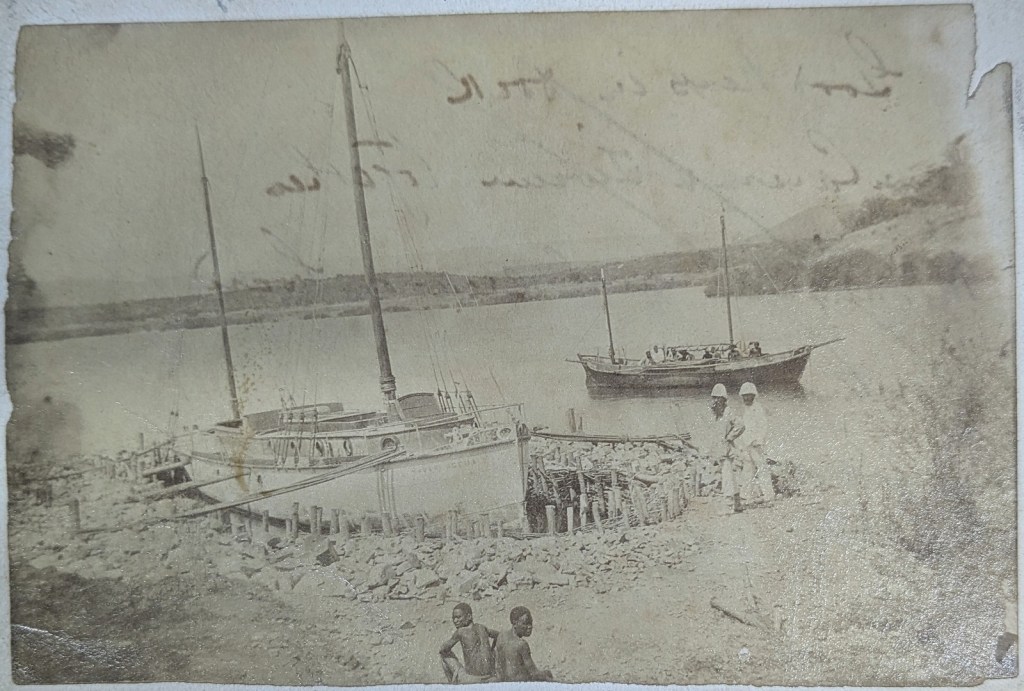

And photos of the letter itself:

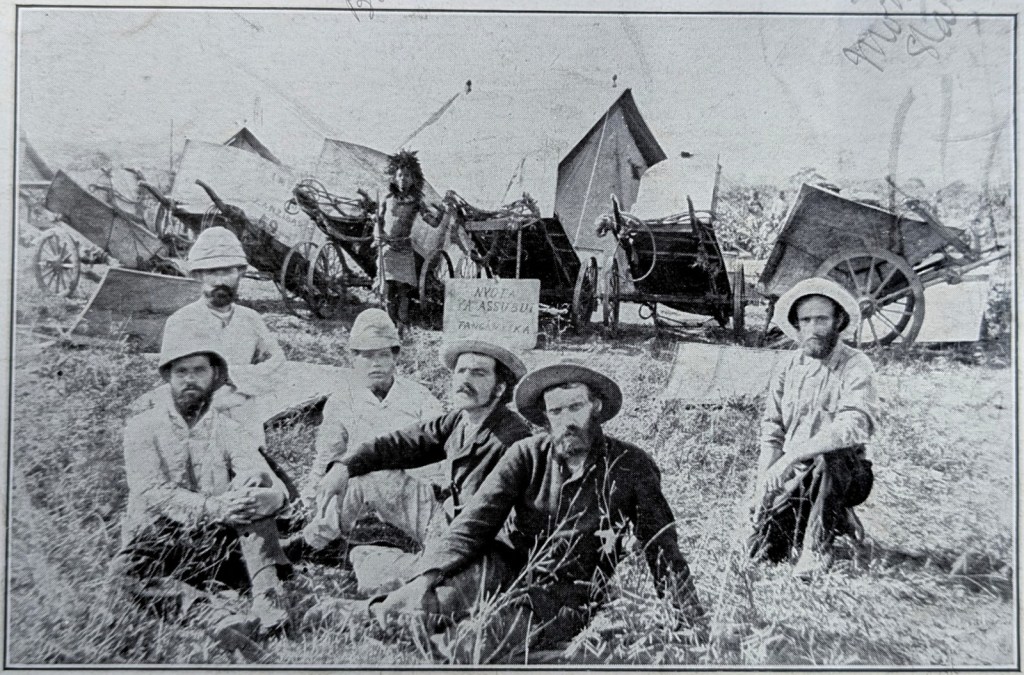

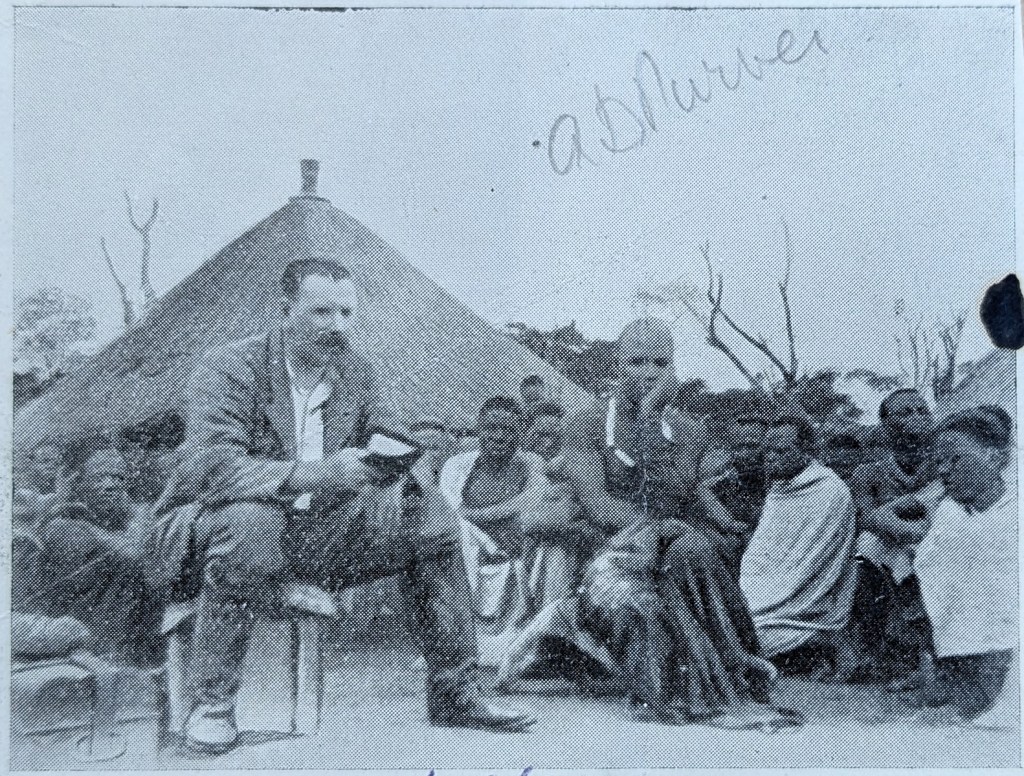

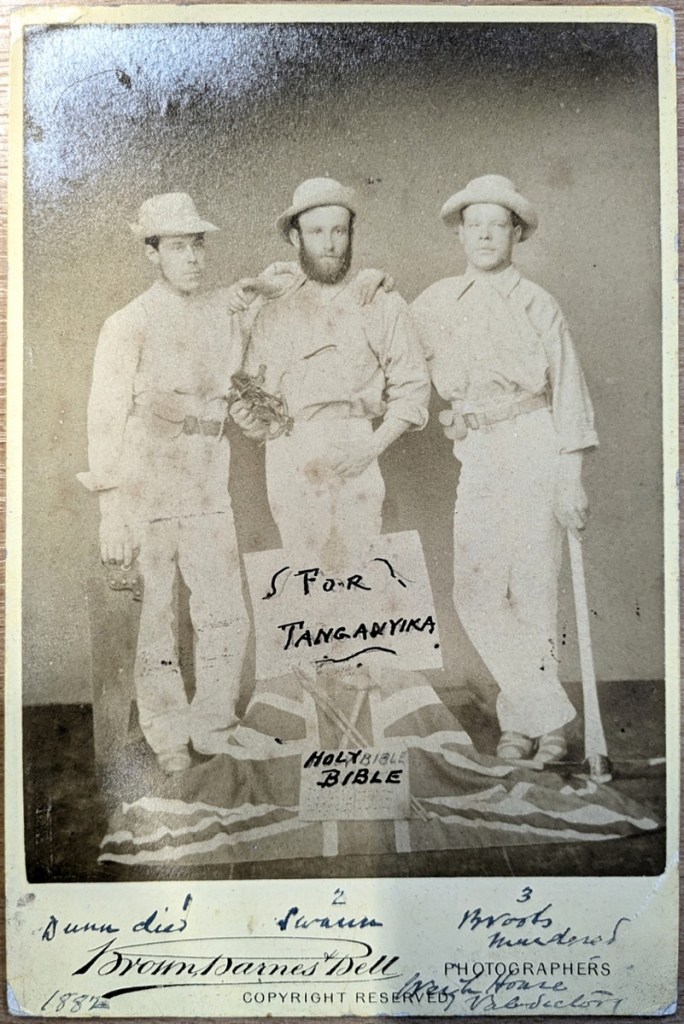

“M.J. Holland” I assume must be Michael James Holland. He worked for Tanganyika Concessions Limited, which was nicknamed “Tanks,” an appropriate moniker for an inherently dispossessive colonialist enterprise. Though still different, it seems to have been closely related to the BSAC. But for our purposes, as you can see from the letter the important bit is that they were putting together the Cecil Rhodes. Loyal readers will recall that I visited the boat’s boiler, which still lies in the village of Kasakalawe right to the west of Mpulungu. I didn’t find it last time I looked, but this page and this page contains more information on the Cecil Rhodes, including pictures of the hulk as it rests on the Tanganyika lakebed.

According to the letter, Tanganyika Concessions was looking for a place to build and anchor the Cecil Rhodes. The LMS was sitting on the best anchorage around so they asked to do a land swap. If my assumption in the previous post that the letter dated July 12, 1900 had something to do with this land swap, then something must have been discussed prior to the above letter, dated five months later. But everything must have worked out between the LMS missionaries and Tanks because according to The Great Plateau of Northern Rhodesia the Cecil Rhodes was launched in October 1901. The above-linked Mr. Codrington described Lake Tanganyika’s merchant marine in a May 1902 article in The Geographical Journal:

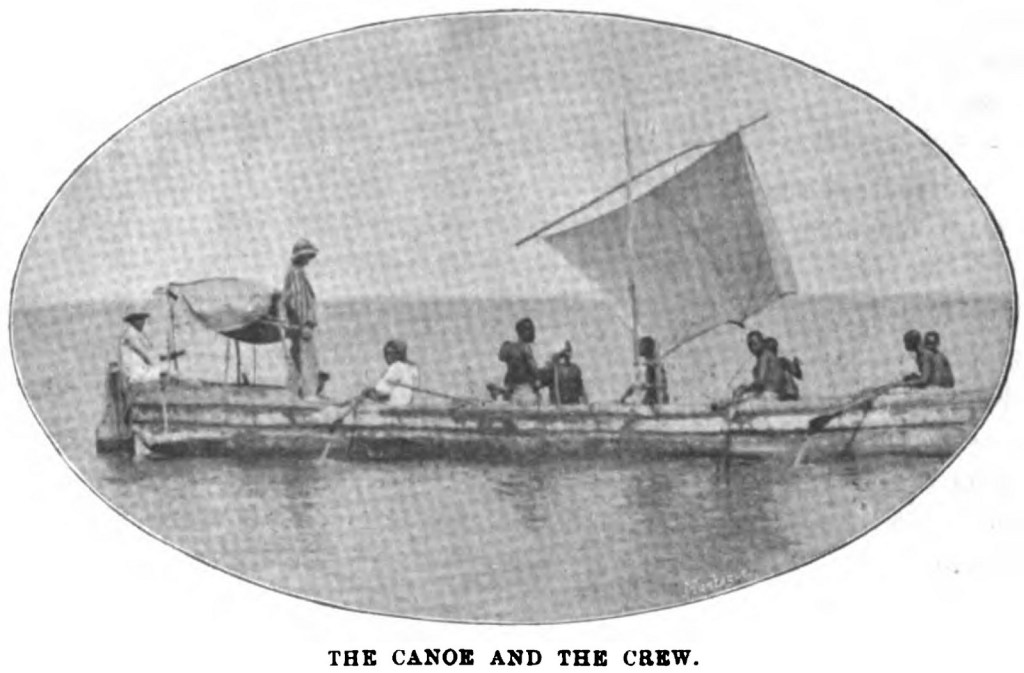

The vessels now plying on Tanganyika are – the “Tanganyika Concessions” steamer Cecil Rhodes (twin screw), with a carrying capacity of from thirty to forty tons; the German Hedwig von Wissmann, with about an equal capacity; the African Lakes Corporation’s steamer Good News, with a carrying capacity of twenty tons; and the Congo Free State schooner, carrying about one hundred tons. Some five or six dhows, the property of Arab and Greek traders, compete in a small way with the European-built vessels. The lake, though said to be more stormy than Nyasa, is considered a safe waterway by the skippers of the vessels, no dangerous rocks being reported. The level of the lake in June, 1901, was 4 or 5 feet higher than in the corresponding month of 1900, the Lukuga outlet having again silted up.

A couple points of the above: by this time the LMS had sold the Good News to the African Lakes Corporation, explaining the ownership status. I did notice the conflicting dates with the fact Mr. Codrington’s journey started in June 1901, before The Great Plateau says the Cecil Rhodes was launched. And finally, before looking into this again I had never heard of the “African International Flotilla and Transportation Company” and so I will have to research more. Nor do I have any idea what the 100-ton Congo Free State schooner could be. So many more questions than answers out of one short paragraph.

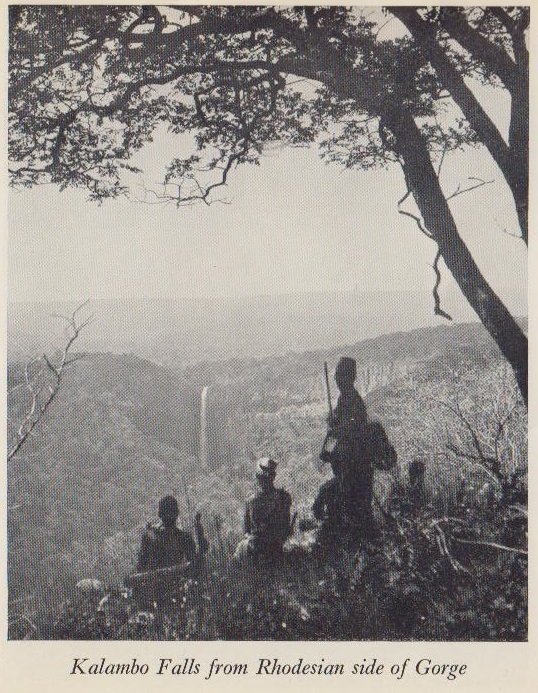

But again back to land swaps. Not only did it all work out for the Cecil Rhodes and Tanks but that land is still where the Mpulungu Harbor Corporation is today. It is not immediately clear to me what the exact corporate lineage is between the Tanganyika Concessions Company and the MHC but I am sure it is interesting. Also very interesting is this cool video about the Mpulungu Harbor Corporation from four years back:

You must be logged in to post a comment.