Reading this week:

- In Quest of Gorillas by William K. Gregory and Henry C. Raven

To make up for a whole bunch of blog posts, I am publishing in post format the biographies I compiled for my world-famous “The Chronicle of the London Missionary Society for all articles relating to their Central Africa Mission from 1876-1905.” I appreciate your patience!

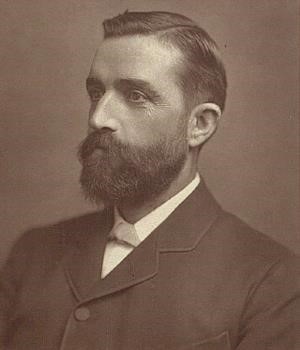

Edward Coode Hore

Born: July 23, 1848, in Islington

Died: April 1912, in Hobart

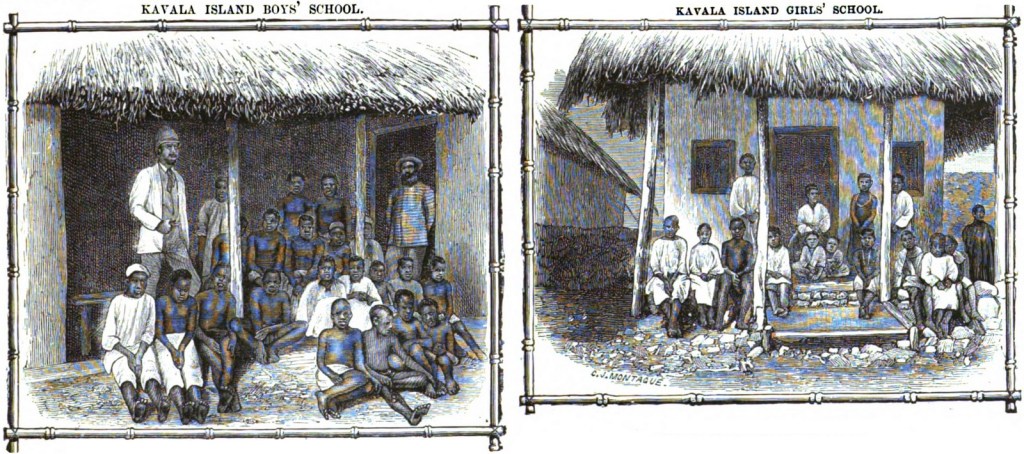

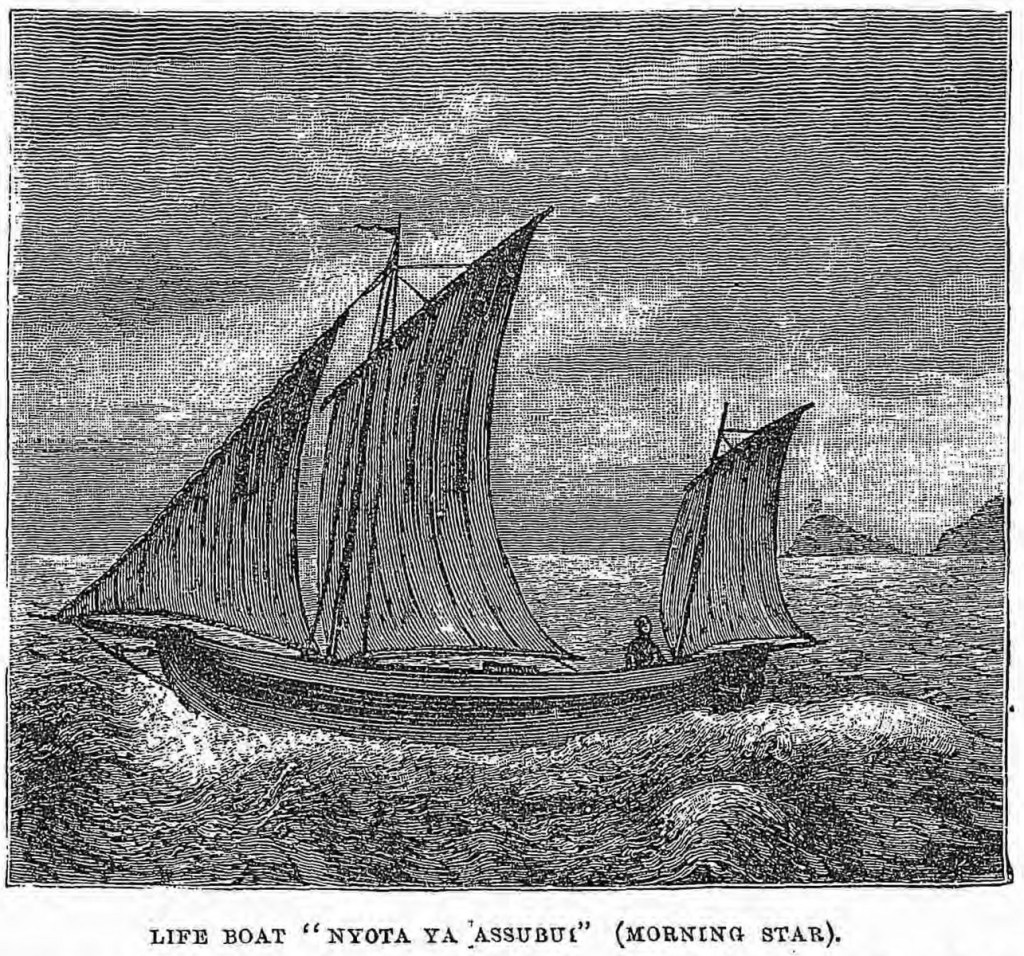

Mr. E.C. Hore departed England for Zanzibar on April 14, 1877 [May 1877] and arrived on August 1. He arrived at Ujiji a year later on August 23, 1878 [Dec 1878]. He explored the southern end of Lake Tanganyika in the Calabash in February 1879 [Jan 1880] and March 1880. Mr. Hore returned to England, departing Ujiji on November 3, 1880 [Jun 1881] and arriving on February 23, 1881 [Apr 1881]. On March 29, 1881 he married Annie Boyle Gribbon and while in England passed the examinations for Master Mariner. On February 4, 1882 the couple had a son, John Edward, nicknamed Jack [Mar 1882]. They departed England on May 17, 1882 [Jul 1882], reaching Zanzibar on June 19 [Sep 1882]. Due to difficulties Mrs. Hore and Jack returned to England, arriving on December 24, 1882 [Feb 1883]. Mr. Hore arrived at Ujiji on February 23, 1883, conveying sections of the Morning Star. He returned to Zanzibar to meet Mrs. Hore and his son Jack, arriving on September 26, 1884 [Feb 1885]. The family arrived in Ujiji on January 7, 1885 [May 1885]. They settled at Kavala Island. They returned to England in 1888, departing Lake Tanganyika in June [Ninety-Fifth Depart] and arriving on October 26 [Dec 1888]. On April 5, 1889, Jack died in London [May 1889]. In April 1890 Capt. Hore departed on a deputation tour [Apr 1890]. Mrs. Hore had a daughter on August 22, 1890 [Oct 1890]. Capt. Hore resigned from the London Missionary Society in December 1890 and visited the United States, returning to England in April 1891. He then joined the London Missionary Society steamer John Williams as First Officer and then Captain from 1893 [Nov 1894] until 1900 [Apr 1900]. The family settled in Tasmania.

Annie Boyle Hore, née Gribbon

Died: April 28, 1922, in Sydney

Ms. Gribbon married Mr. Edward C. Hore on March 29, 1881 and on February 4, 1882 had a son John Edward, nicknamed Jack [Mar 1882]. They departed England on May 17, 1882 [Jul 1882], reaching Zanzibar on June 19 [Sep 1882]. Due to difficulties Mrs. Hore and Jack returned to England, arriving on December 24, 1882 [Feb 1883]. Mrs. Hore and Jack departed again on June 11, 1884 for Quelimane [Jul 1884]. The family arrived in Ujiji on January 7, 1885 [May 1885]. They settled at Kavala Island. They returned to England in 1888, departing Lake Tanganyika in June [Ninety-Fifth Depart] and arriving on October 26 [Dec 1888]. On April 5, 1889, Jack died in London [May 1889]. On August 22, 1890, Mrs. Hore had a daughter [Oct 1890], named Joan1.

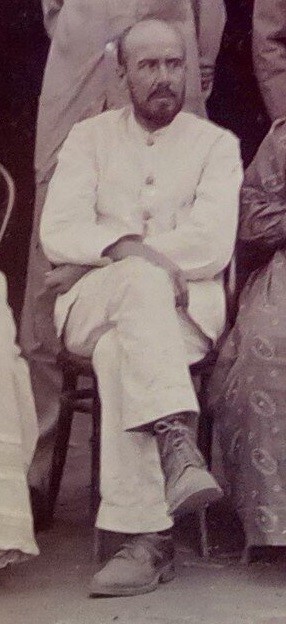

Walter Hutley

Born: January 18, 1858, at Braintree

Died: 1931 in Adelaide, South Australia2

Mr. W. Hutley had six years’ experience as a builder and joiner3. Appointed to the Central Africa Mission as an artisan missionary, he left England on April 14, 1877 [May 1877]. He arrived at Ujiji on August 23, 1878 [Dec 1878]. He departed Ujiji October 22, 1879 alongside Rev. W. Griffith to establish a station at Mtowa [Mar 1880]. He returned to Ujiji in November 1880. Due to failing health, he departed Ujiji on January 11, 1882 and arrived in England March 1 [Apr 1882]. In February 1883 Mr. Hutley married Laura Palmer, the sister of Dr. Walter Palmer4. His connection with the London Missionary Society ceased in June 1883. In 1884 the couple moved to Adelaide, South Australia.

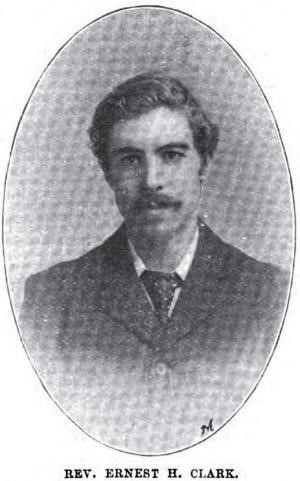

Rev. Harry Johnson

Born: December 17, 1868, at Market Harborough

Died: 1964†

Rev. Harry Johnson studied at Cheshunt College and was ordained on April 23, 1896 [Jun 1896]. He departed England on May 15, 1896 [Jun 1896]. He worked at Kawimbe for one year and then transferred to Kambole. On August 26, 1897, he married Minne A. Allen in a ceremony presided by Commissioner Alfred Sharpe [May 1898]. The couple had a daughter on July 23, 1898 [Dec 1898] and a son on December 21, 1899 [May 1900]. The family departed for England on furlough on June 1, 1900 [Jul 1900], arriving on August 18, 1900 [Oct 1900]. There they had another daughter on August 23, 1901 [Oct 1901]. Rev. Johnson may have returned to Central Africa alone, departing England on April 30, 1902 [Jun 1902], and arriving back in England on January 6, 1905 [Feb 1905]. He visited Australia on a Deputation tour in 1906 and then became a pastor in Bradford before finally retiring in New Zealand†.

Minnie A. Johnson, née Allen

Died: March 10, 1915, at Christchurch, New Zealand

Ms. Allen departed England on June 8, 1897 [Jul 1897] and married Rev. Harry Johnson at Zomba on August 26 [May 1898]. The couple had a daughter on July 23, 1898 [Dec 1898] and a son on December 21, 1899 [May 1900]. The family departed for England on furlough on June 1, 1900 [Jul 1900], arriving on August 18, 1900 [Oct 1900]. There they had another daughter on August 23, 1901 [Oct 1901]. Mrs. Johnson retired in New Zealand with her husband†.

Notes:

Unless otherwise noted, missionary biographies are derived firstly from London Missionary Society: A Register of Missionaries, Deputations, Etc. From 1796 to 1923, prepared by James Sibree, D.D., Fourth Edition, published by the London Missionary Society, London, 1923. Brackets with [Month Year] indicate the issue of The Chronicle of the London Missionary Society which records the preceding event. Information denoted by a dagger (†) is from Christian Missionaries and the Creation of Northern Rhodesia 1880-1924, by Robert I. Rotberg, published by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1965. Other sources are denoted by a footnote.

1 “Captain Edward Coode Hore (1848-1912): Missionary, Explorer, Navigator, and Cartographer, Part 1,” by G. Rex Meyer, Church Heritage, March 2013.

2 The Central African Diaries of Walter Hutley 1877 to 1881, edited by James B. Wolf, published by the African Studies Center, Boston University, 1976.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.