It was time for us to leave Edinburgh and so we got on an airport transfer bus and picked up a rental car, marking the first time I had driven a stick shift with my left hand. Our final destination was Skye but instead of driving there all in one day we were going to stop in Fort William. This gave us time to see in a leisurely way some of the sites, and my top priority was the David Livingstone Birthplace museum. I have been to the David Livingstone deathplace, and so visiting here meant, in physics terms, that I would have experienced Livingstone’s entire life. Despite it being my top priority I had not expected much of the place. However, having visited other David Livingstone museums and now this one I am willing to say: this is the greatest museum to David Livingstone in the world.

The reason I had not expected much was both bad assumptions and the online reviews. Like, I have been to the George Washington Birthplace National Monument and it didn’t really have a lot about George Washington. Or that’s how it seemed to me, though I visited in the last hour of the day it was open so maybe I did not look as closely as I could have, but it’s mostly a farmstead (seems to be a trend). David Livingstone was born at the Blantyre Cotton Works, so based on the George Washington experience I was anticipating a museum mostly about how cotton works work. The other factor is that the reviews my super amazing wife looked at mostly cited it as a nice place to walk a dog.

And you know what, it does look like a really nice spot to walk a dog. You drive through a pretty little village/suburb to get to the museum, and as you turn into the parking lot there is a big field with trees on the edges and a path that leads down to the river (the cotton works being where they are so they could be powered by that river). They also have a lovely café where you can get tea or lunch (they have full table service! At a museum café!), and a playground for kids (they had one of those pirate ship play-sets which one sign said was inspired by the boats that Livingstone used on the Zambezi, and like, uh-huh). But we were not here for leisure, we were here for history, and so in we went to the museum.

The museum is extremely well done. Although now juuuuust about a century old, back in 2017 it got a £6 million grant and did a lot of work on conservation and updating the exhibits, reopening in 2021. The museum is laid out chronologically through Livingstone’s life. Actually a bit to my disappointment there is not much at all about the cotton works themselves, though do they have on display a spinning mule and a model of what the cotton works would have looked like while Livingstone was there. When they talk about the works it is in the context of David working there as a boy and young man, saving up to put himself through medical school.

On our visited we unexpectedly joined a guided tour when the tour guide invited us along. The one other person touring with us was apparently related to Livingstone and had met with Chief Chitambo (the current one) in Zambia. She had brought along some photos to give to the museum. The biggest advantage of having joined the tour and there being only three of us is that the guide let us past the rope barrier into the very room where Livingstone was born (and where he lived with his grandparents, parents, and siblings, all in that one room – and it was some of the nicer accommodations). I had been on the very spot where Livingstone died and now I was on the very spot where he was born (very completionist of me).

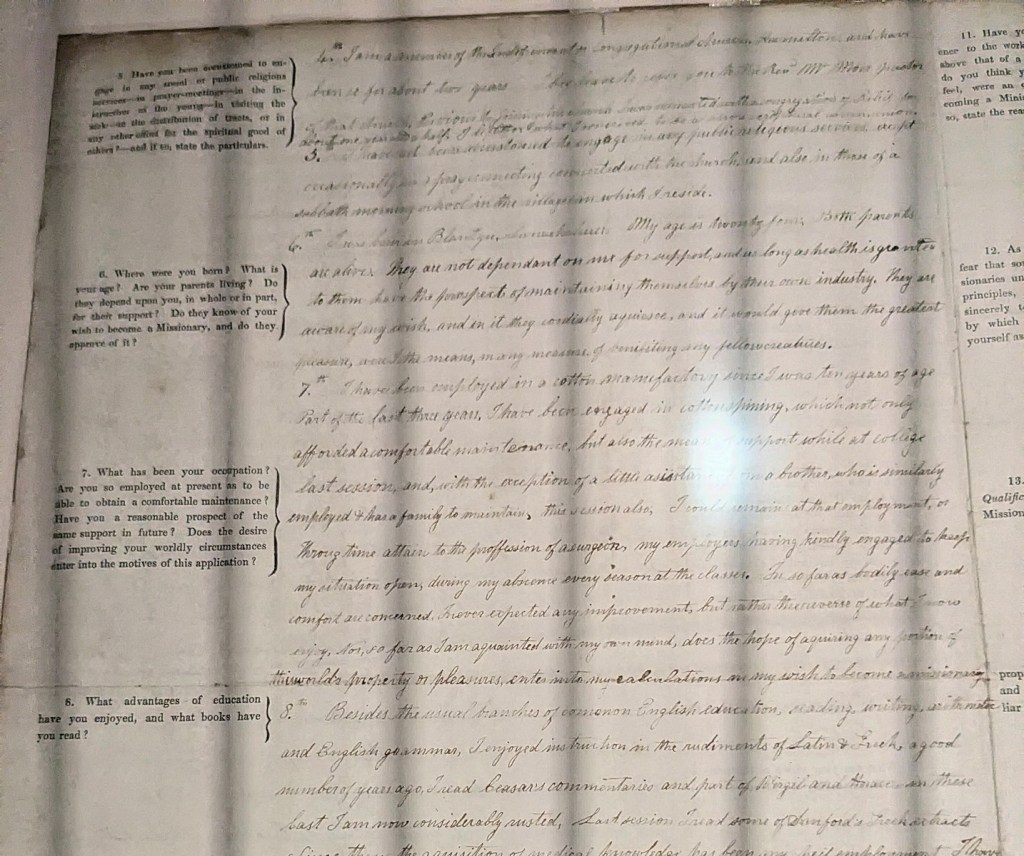

From there they talk about his early life and education, and proceeding through is career. Livingstone had decided he wanted to become a medical missionary and so started working toward that. The museum has some displays dedicated to his medical training, including his surgical instruments. For Livingstone, it was a bit of an accident he wound up in Africa at all, originally wanting to go to China and only being prevented by the First Opium War. He joined up with the London Missionary Society (they have his application at the museum!) when the cotton works wouldn’t have him back, forcing young David to get funding from elsewhere. Although I have read Tim Jeal’s biography, these were all new facts to me.

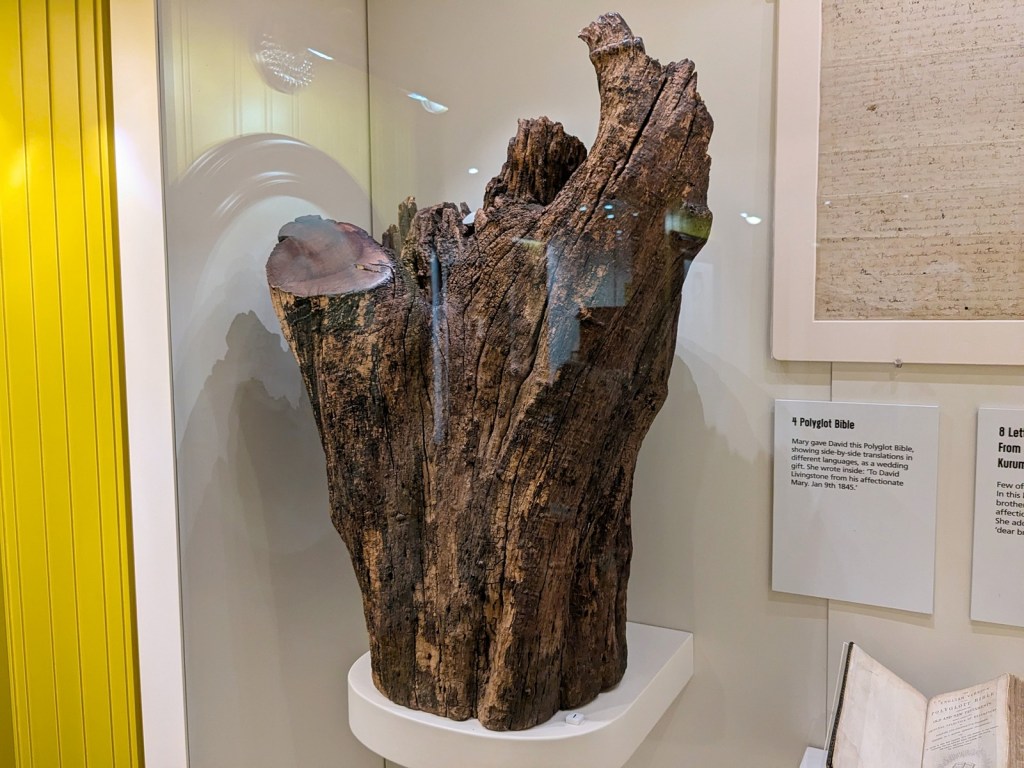

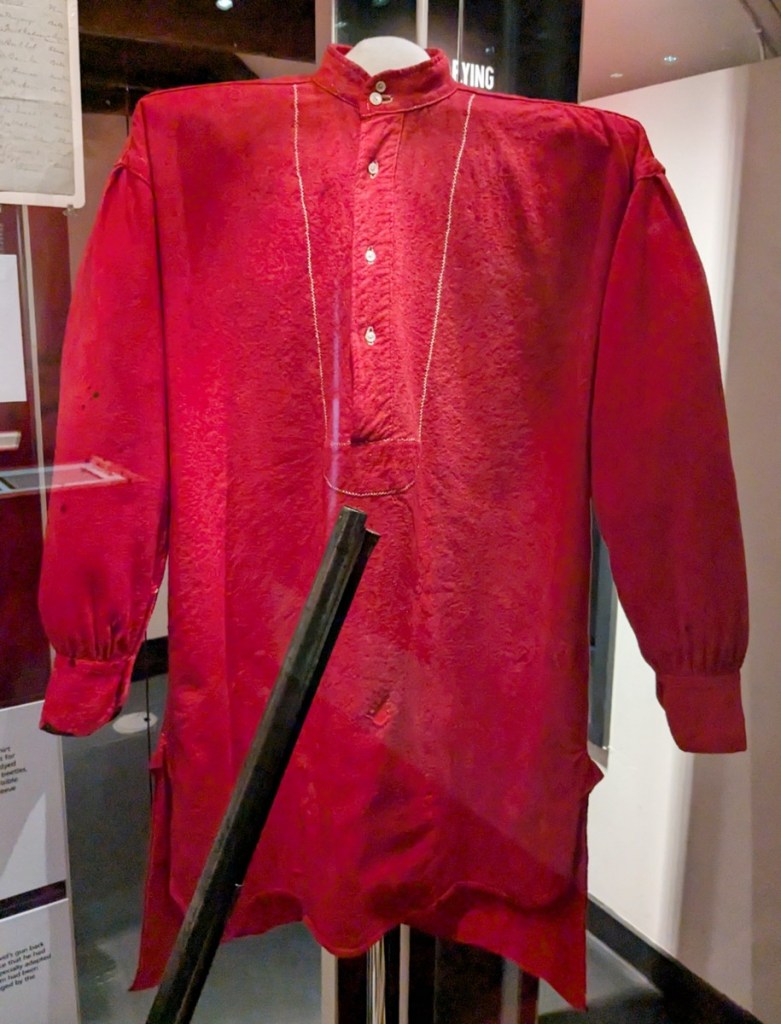

Throughout they have some interactive displays clearly meant to appeal to a slightly younger audience, but overall it is a really in-depth and serious museum about David Livingstone’s travels and impact, with special focus on the people that helped him along the way. They do this through what is an astounding array of artifacts. Like George Washington, David Livingstone was clearly the sort of person that inspired admirers to collect relics. Many of these relics were clearly put in the museum to appeal to me, specifically, like various navigation instruments that Livingstone used. But I mean they go deep. They got a chunk of the tree under which he proposed to his wife, Mary Moffat. They got a chunk of David and Mary’s house in Kolobeng. They got David’s forks and spoon even, and they have the very shirt that Livingstone was wearing when he met Stanley. They got everything.

On this particular day and throughout the tour we kept spotting various bits of the walls that had been covered up. Our tour guide explained that recently a protester had come in and written on the walls about colonialism and Palestine. My initial reaction was that the anger was a little misplaced towards Livingstone, seeing as he mostly seemed to want to help people. But that doesn’t necessarily mean much. The whole reason I got interested in the London Missionary Society in the first place, after seeing what info they had on the Mambwe, because they are a case study I think of people doing development work out of a fervor to help people. Their work wound up shaping the way colonialism in central Africa played out, and over a hundred years later we can look back with some perspective, useful as we continue to do development work out of a fervor to help people. So that doesn’t absolve you.

The museum also works to paint a holistic picture of the man. The obvious case is the failure of the Zambezi expedition, and the museum talks about the impact that had on his reputation. I also learned from the museum and the guidebook that Livingstone wrote out of his narrative at least sometimes the efforts of other people, such as William Cotton Oswell and Mungo Murray. Those men travelled with Livingstone to be the first Europeans to see Lake Ngami, but Livingstone wrote to the Royal Geographic Society taking all the credit. And then there is of course his wife Mary. Mary was born and raised in South Africa, and all her family was there. Although she joined him on his early travels, he eventually had her go live in the United Kingdom, shuffled between various houses while he went exploring in Africa. He could have treated her a lot better and eventually realized this after she died, but man, that is a revelation to have before you leave your wife to raise your children for like five years while you go trekking.

These thoughts were on our mind as we finished the tour (the room on his legacy is the last room of course so it is designed to be on your mind. We head out to explore the rest of the grounds, including walking down to the bridge across the river. It is a lovely place to consider the impact someone can have on the wider world, whether those impacts are intentional or not. What I can say in the end is that the Birthplace museum is a must-visit spot for anyone interested in David Livingstone, early European travels in Africa, or the history of Europe in Africa in general. Or if you need a really nice spot to walk your dog.

You must be logged in to post a comment.