The timeline of the official date of this post and of subsequent posts aren’t going to make a lick of sense but that is what happens when I am behind on writing and I feel bad about it. But anyway for undisclosed reasons I recently found myself in Brussels for a day. I had a friend to see and I wouldn’t ever tell her this but she was actually only my second priority for the day, the first priority being seeing the Royal Museum for Central Africa!

I learned about the museum from Adam Hochschild’s book, King Leopold’s Ghost (available in the gift shop). He does not exactly speak highly of the museum in the book, but given it is a repository of so many artifacts from central Africa (and more specifically the DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi), I wanted to go, trusting myself to contextualize what I was seeing appropriately. Since the publication of King Leopold’s Ghost, and possibly spurred on by it, the museum closed down for five years between 2013 and 2018 to rethink and revamp its collections and displays, and Adam Hochschild had a chance to revisit it, which he wrote about in The Atlantic. In the article Adam describes taking “one of Europe’s loveliest urban journeys” to the museum via the trolly. I was so excited to see the museum that I took a slightly different path, going to the museum via the bus straight from the airport (still an extremely lovely trip). I think I was the very first guest in the museum that day.

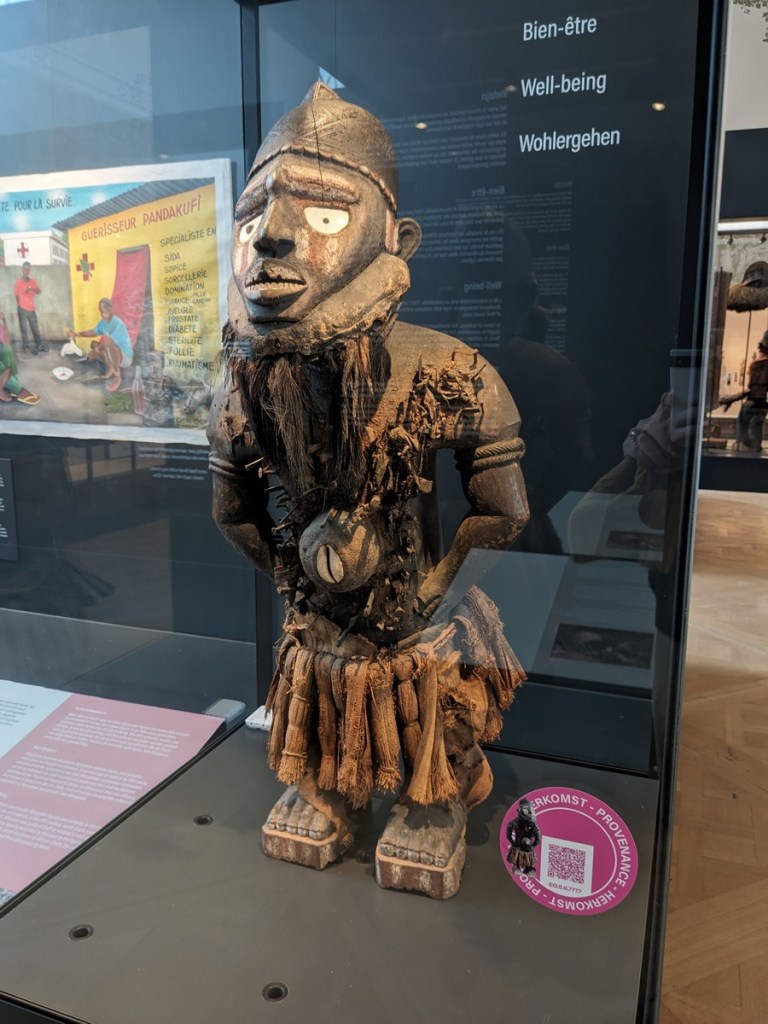

I knew the museum had been revamped and had reopened in 2018, so was hoping that it would embrace more modern views of what this sort of institution ought to be. After entering the museum the very first exhibit I saw was “Rethinking Collections,” and the very first artifact I saw in that very first exhibit was the dude above. A more proper name for this dude is “a kitumba sculpture stolen by the Belgian tradesman Alexandre Delcommune from the Congolese chief Ne Kuko” (okay full disclosure the very first artifact you actually see is in the hallway to that exhibit, which is this extremely cool pirogue) (as a second parenthetical I was going to call the pirogue “potentially problematic” and alliteration aside that applies to every artifact so I am going to skip it generally). There is of course a sign next to the kitumba sculpture and I was worried about the tone it was setting. The sign notes that Ne Kuko asked Delcommune for the statue back, and Delcommune refused. The sign then notes that a descendant of Ne Kuko has asked for the statue back more recently, but that the museum hadn’t given it back then either. Then the story on the sign ends, leaving me wondering, you know, why the heck they didn’t give it back. Maybe I missed it in the exhibit itself but it wasn’t until I was able to review the museum’s page on the statue (linked above), where they note that “there is still no legal framework for the restitution of objects and human remains,” explaining why they still have it.

I am in many ways very sympathetic to this excuse, being a dedicated government bureaucrat myself, and if I was a museum administrator that would kind of be the end of the story for me. But as a society that excuse is awfully thin. Laws are all made up, you know? We can just change them. Returning to the moment in the exhibit, I was just left with a sign that said they had turned down requests for restitution twice, which wasn’t encouraging. The purpose of the “Rethinking Collections exhibit was to ask “How do we trace the origin of collections? What new insights can be gleaned from these provenances? And what should become of such collections, within and beyond museum walls?” For this visitor at least it missed the mark a bit, but as Adam Hochschild pointed out in his Atlantic article, these signs in this museum are the result of compromises. As we evolve maybe we’ll get closer to a better answer.

Having gone through that exhibit, I finally went upstairs into the main building itself (you enter through an annex and then go through an underground hallway). The building was first opened in 1910, purpose-built for this museum, and it is constructed as like a palace to display the grandeur of Belgian colonialism. Let me tell ya it is certainly awe-inducing. I was overwhelmed by the sheer mass of the collection. The picture above is just one small corner and I think it would take days to give every artifact its due consideration. It’s in a big square, with two layers of rooms, and I chose to go through the museum counter-clockwise. This had me starting with the I guess you would say ethnographic portions of the museum. As you can see above and below these displays are chock full of artifacts collected during the colonial era, and reflect the western interest in the more “exotic” aspects of the Congo basin cultures the colonialists were encountering.

I had been familiar with much of the sorts of types of objects on display, having done my reading and visited places like the Smithsonian Museum for African Art. The nkisi mangaaka I actually recognized from the book Kongo: Power and Majesty, which my super amazing mother-in-law had given me for Christmas last year, so that was a bit like seeing a celebrity in person. However a whole category of objects I had no idea existed were what the museum called “currency in the shape of throwing knives.” There is a spectrum I think between actual throwing knives and currency in the shape of throwing knives, but some examples are below. They had even more elaborate versions but those did not photograph well on my smart phone camera so you are left with these ones that I think are slightly closer to the “actual throwing knives” part of the spectrum, but not by far (there’s also a ceremonial axe). The sheer artistry of the metalwork in these knives (along with, you know, every single other metal object in the museum) is overwhelming and extremely cool and I dunno man if I was a young bride-to-be in Congo I think I would want my husband to come up with some of these things in order to bond our families together, you know? They had some really nice hoes as well but you also gotta throw in some of these knives man. They’re so cool.

One of the more impressive things which I did not expect to see (besides the knives) were several gigantic maps of central Africa, depicting various aspects of Belgian colonial interests. I used a selfie in the picture below to try to give you some sense of scale, but man it doesn’t hit. These things are huge. The building itself is huge, with 50-foot ceilings (or something like that, they are TALL), and these maps go from nearly the floor to nearly the ceiling. The one above depicts the routes various European travelers took through Africa (you should be able to see Cameron and Livingstone labelled above). Others depicted political boundaries or natural resources. As a man who likes maps (i.e. I guess a man), these were about the mappiest maps you could map. They were scattered throughout the building and provided impressive backdrops to the displays.

If I recall correctly, the displays the particular map above were backdropping were, fittingly, about the various horrors of colonialism. It is quite the mix of artifacts. I was excited to spot a sextant and then a little stunned to discover it was owned by Stanley. I have read about Stanley a lot and he seems almost not real. Then you come across an actual object he used, one I’m familiar with. That same feeling went for the objects below associated with Tippu Tip. Tippu Tip! When I was in Zanzibar we went to a Chinese restaurant that I later think I figured out what in Tippu Tip’s old house, which doesn’t help make the man seem real. My super amazing wife and I have been to Rick’s Cafe in Casablanca (I will write about that eventually), and you know that’s fake, and so I guess Tippu Tip’s house felt the same? But here you have a necklace supposedly owned by him (link in the caption for more details), and a dagger owned by his son. The actions of Tippu Tip and his fellows was used to justify so many of the actions of the Europeans took in Africa that again he is much larger than life, too large to have been real, and yet here is his stuff. Lest the section is entirely the Big Man theory of history, it also gets down to more of the brass tacks of colonialism. They have several examples of the hippo-hide chicottes (whips) on display, along with photos of the horrors inflicted on the people of the Congo.

The next part of the museum was about the natural resources in central Africa:

Another criticism of this and similar museums as an institution that I hadn’t thought about too deeply until I read the Atlantic article is the fact that people, animals, and geology are all lumped together into a single museum. This is not a pattern that is replicated in museums about more “western” subjects, with western peoples getting their own museums separate from western animals and western geology. The Royal Museum addresses this a little bit obliquely, in some signs about the “crocodile room” (pictured above). They’ve preserved the crocodile room to look like it would closer to 1910, meant to catalogue all the items under Belgian colonial rule, both natural and man-made. The paintings lining the upper parts of the walls are also meant to depict an idealized Congo, peaceful and prosperous.

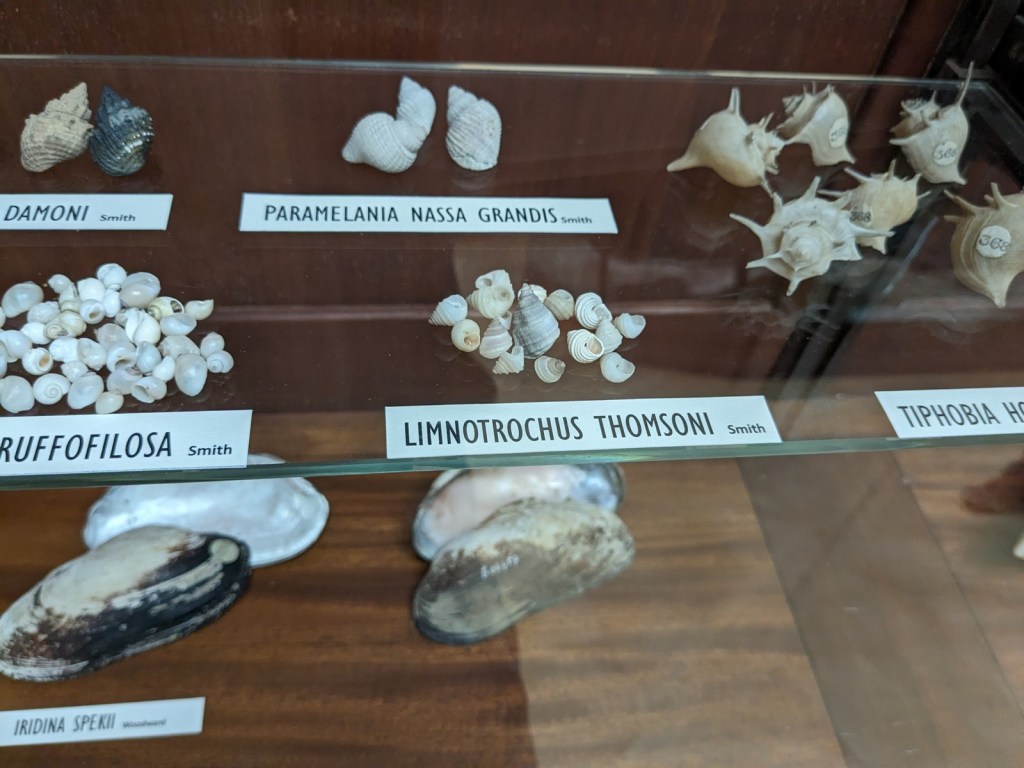

That being said it was neat to see the different animals and shells. Some of the more interesting things for me (pictured above) were a tilapia (because we’re big tilapia fans around here), along with shells named after various famous British travelers in Africa. One oversight I noticed is they neglected to include (as far as I could tell) any examples of the most important specimens, my main man Ed Hore’s Tiphobia horei. Later on they also had examples of more robust fauna:

Also notable in this general section was a whole room dedicated to the mineral resources of the country. They had discussions on the some of the political implications of the exploitation of these minerals from the DRC, but as these rocks sit there sterile on a shelf it is hard to imagine the suffering they can help perpetuate:

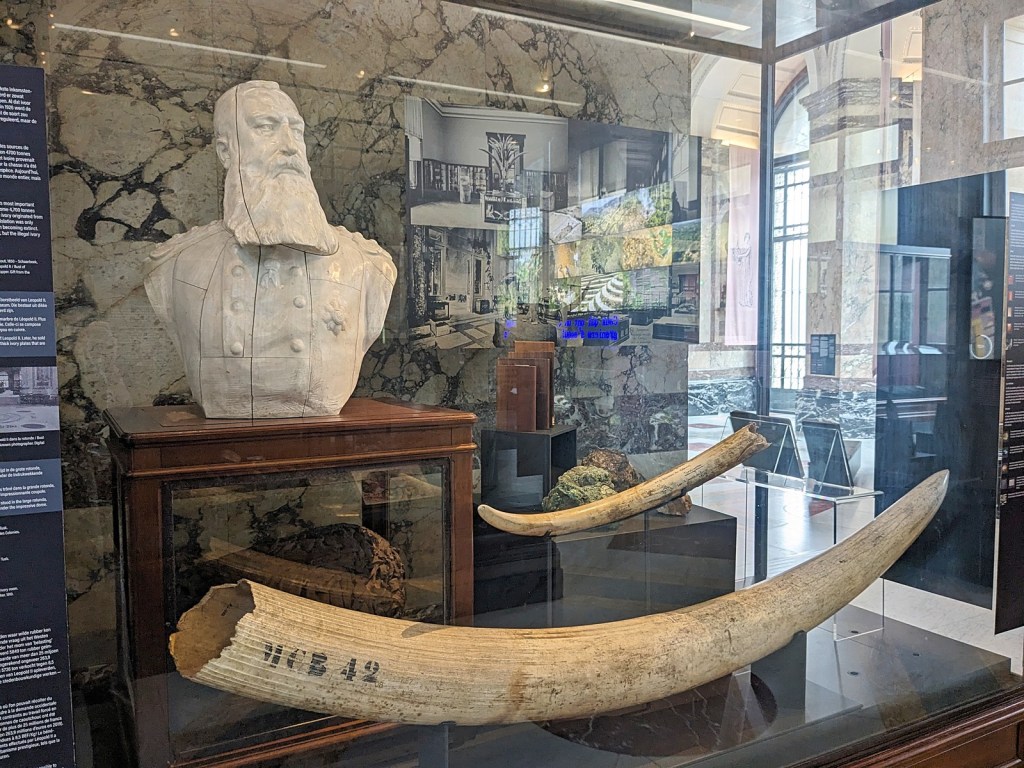

The focus of the section on the natural resources of the Congo was the “paradox” it creates, where DRC is sitting on trillions of dollars worth of minerals and other resources and yet still remains poor due to exploitation. The section had a long discussion on what those resources are and how they have been exploited and what resources the Congolese people themselves use. As can be seen from the ivory bust of King Leopold below, that all is put in stark terms.

In the second half of the museum, which I didn’t really get great pictures of because at this point I was exhausted just from the sheer scale and trying to see it all, the exhibits turned towards the more modern eras of the Congo and its relationship to Belgium. A particularly interesting section talked about the Congolese diaspora in Belgium post-independence, and another highlighted the relationships between traditional music and modern-day Rumba. But the single most powerful section trying to address the modern and historical relationship of Belgium and the Congo was in the rotunda.

The Grand Rotunda of the museum was designed (like the rest of it), to showcase the glory and what have you of the Belgian empire. Besides being a gigantic and impressive room, it features four gilded bronze sculptures by Arsène Matton. The sculptures represent a colonial vision, with the Belgians presented (according to the sign) “as if there had been no civilization beforehand… African women are sexualized. An Arabo-Swahili slave trader tramples a Congolese who tries to protect his wife. It is clichéd colonial propaganda, but it is still effective more than a century later.” Apparently “the statues in the niches are part of the protected heritage building and may not be removed.” Like I said above the legal excuse I think is a pretty thin one but in this case it meant the museum was forced to be a little more creative in how it addressed the statues.

The art project they have done instead is called RE/STORE, and for it “the museum invited Congolese artist Aimé Mpane to create a project that would serve as a counterweight.” The result are these translucent banners hung in front of the statues that speak to them and provide an alternative vision of colonial-era Congo, one where there is civilization and the horrors of colonialism aren’t excused. I thought it was really cool how instead of just acting as a counterweight the banners really speak to and respond to the statues themselves for a super stunning effect, and is a great example of how to communicate with these previous idioms of how we view our relationships with other peoples.

And that was my visit to the Royal Museum for Central Africa. The place is far from perfect but they seem to be trying, and I hope we can put in place in the near future the institutions needed to bring some justice to the colonial relationship with Africa. Everyone should be able to see the treasures the museum holds, especially the people that should rightfully own them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.