Reading this week:

- The Central African Diaries of Walter Hutley edited by James B. Wolf

- Mirambo of Tanzania by Norman R. Bennett

Alright I ended the first part of the story of our Ujiji Walking Tour a bit abruptly there after trying to impress you all with various links to obscure and not-so-obscure websites in an effort to establish my independent researcher bona fides. I’ve gathered my thoughts however so now I hope you’ll continue with me as I recount the rest of the particular adventure.

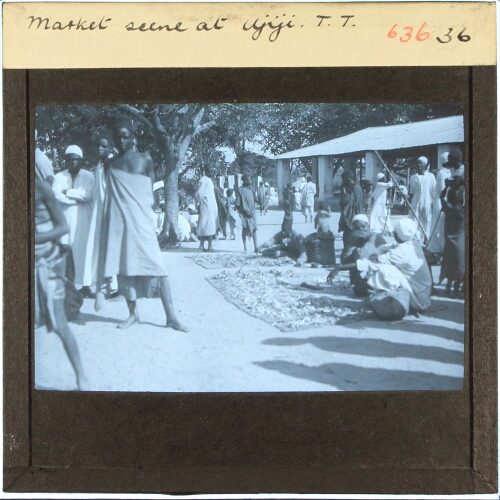

After the location of Tippu Tip’s house we walked just a little farther up to the location billed as the former slave market. I have no real way I think to verify this. I did not mark this on the map as we were walking around but I think it is here. The structure is not new but I am not so sure it is 1880s old (here is a picture from Kigoma Eco-Cultural Tourism’s Instagram feed), so I will take it more as the location of the former slave market. I would say though the structure is at least 1920s old because there it is in the above picture (I think) in a photo taken by the Gordon-Gallien Expedition. According to London Missionary Society lore the daily slave market stopped as soon as the missionaries pitched up in Ujiji (openly anyways, the trade in enslaved persons according to the missionaries just moved to private spaces).

Peter, our wonderful tour guide, told us the small shops around the market were originally slave pens which, again, I am not so sure is true, but poking around one of those shops was the most fun experience. I had noticed some pots out front and asked about them. Peter explained some were for cooking and some were for rituals, and we went over to check out the shopkeeper’s other wares as he was setting up for the day. In the “rituals” category Peter pointed out the different spears available, some with wooden shafts and some spears entirely made out of metal (in this case repurposed rebar); I didn’t really understand this until we went to the museum later but the all-metal spears are apparently for rituals and other traditional ceremonies, while the wooden-shafted ones are for normal spear purposes. I was tempted to get one but it would have been too big for my suitcase. The shop also had barkcloth which was very cool to see in the wild and that got my super amazing wife jazzed because it was a textile she hadn’t known about. Peter modelled some of the barkcloth in the traditional manner. I feel bad I didn’t get anything from the stall but I wasn’t sure this was an appropriate moment to start shopping as we were in the midst of a tour. The most tempting thing was a very cool looking boat where the only drawback was that it said “Burundi” on the side, which although a wonderful example of the connected lacustrine economy would have been confusing on my shelf.

From the market we wound our way up through some gorgeous gardens to the top of the hill. Here I kept looking over my shoulder because I wanted to recreate the below engraving but with a photo. The scan I have here comes from Ed Hore’s book Tanganyika: Eleven Years in Central Africa. I think I will address this more fully when I talk about the museum, but one thing I wanted to do on this trip was figure out where the LMS’ mission house was, and I thought maybe discovering the perspective of the below engraving might have helped. I have since figured out the engraving is more of a stock photo than anything related to the LMS, because it was originally used to illustrate a story about Stanley in The Graphic in 1890. I did not get as expansive and unobstructed view as I had hoped (I was tempted to ask someone if I could go on their roof but thought better of it) but the below ain’t too shabby I think; you can see Bangwe island jutting out from the peninsula and the rolling hills. Next time I visit I’ll figure out a way to do a better job.

At the top of the hill we were winding up we suddenly swap denominations to come across a Catholic church. I know less about this church than I thought I did, specifically when it was built. Although the LMS missionaries got to Ujiji to settle first, the White Fathers were only five months behind them arriving in January 1879. But that doesn’t reveal when the church was built. Of the two plaques on, one commemorates the White Fathers arriving in 1879 and the other I can’t tell what it means. Maybe that the church was built in 1935? Also next to the church is the former mission school which is now a public school but retains its fancy brickwork.

Our walking tour of Ujiji ended on the Tabora Road, or the “trail of tears” as Peter told us it was known. This moniker derives from the fact it is the old caravan route down which ivory and enslaved persons would have been exported (there’s a lot of scholarship that adds nuance to that) and explorers/missionaries/colonialists arrived. The road was lined with large mango trees, again purportedly planted by enslaved persons to provide shade along the route. It was very interesting to me to confirm that this was the road along which all these people would have arrived in Ujiji, especially having seen as we came the other way the crest of the hill and view of the lake it would have provided. We walked along for a bit as we passed different small shops and houses and people going about their daily business along what is still an active path for commerce and travel. It was compelling to me to imagine setting out from here to Tabora and all the way back to the coast as all those caravans would have done, but before we could take that plunge we met back up with Elizabeth, piling into the car to head back down to the lake and the Livingstone Memorial Museum.

You must be logged in to post a comment.