Reading this week:

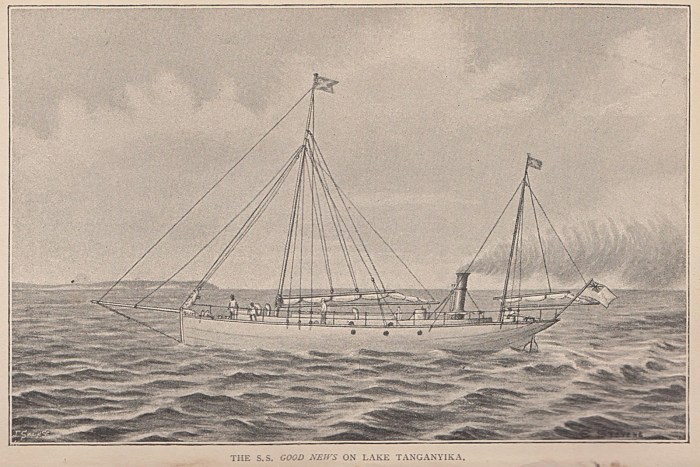

- Tanganyika: Eleven Years in Central Africa by Edward Coode Hore

- The Road to Tanganyika edited by James McCarthy

- Brazza, A Life for Africa by Maria Petringa

One of the interesting parts lately of transcribing the Chronicle is going through the book reviews. It was here I discovered the existence of the book To Lake Tanganyika in a Bath Chair, written by one Annie B. Hore.

I had not given a whole lot of thought to Annie until this point, and that is really an unforgiveable and glaring oversight on my part. She was born on April 8th, 1853 as Annie Boyle Gribbon, the daughter of a prosperous merchant. Annie enters our narrative when she married Edward Coode Hore on March 29th, 1881, while he was on his first home leave after becoming a missionary on the London Missionary Society’s Central African Mission.

I have been trying to dig up information on Annie and besides what I get from the Chronicle, a lot of what I will present here is from a thorough biography of Captain Hore written by Dr. G. Rex Meyer and published in Church Heritage. Dr. Meyer is first cousin twice removed of Annie. It was of course very foolish of me to overlook Annie because she does of course pop up all the time in the Chronicle, albeit it only ever as “Mrs. Hore.”

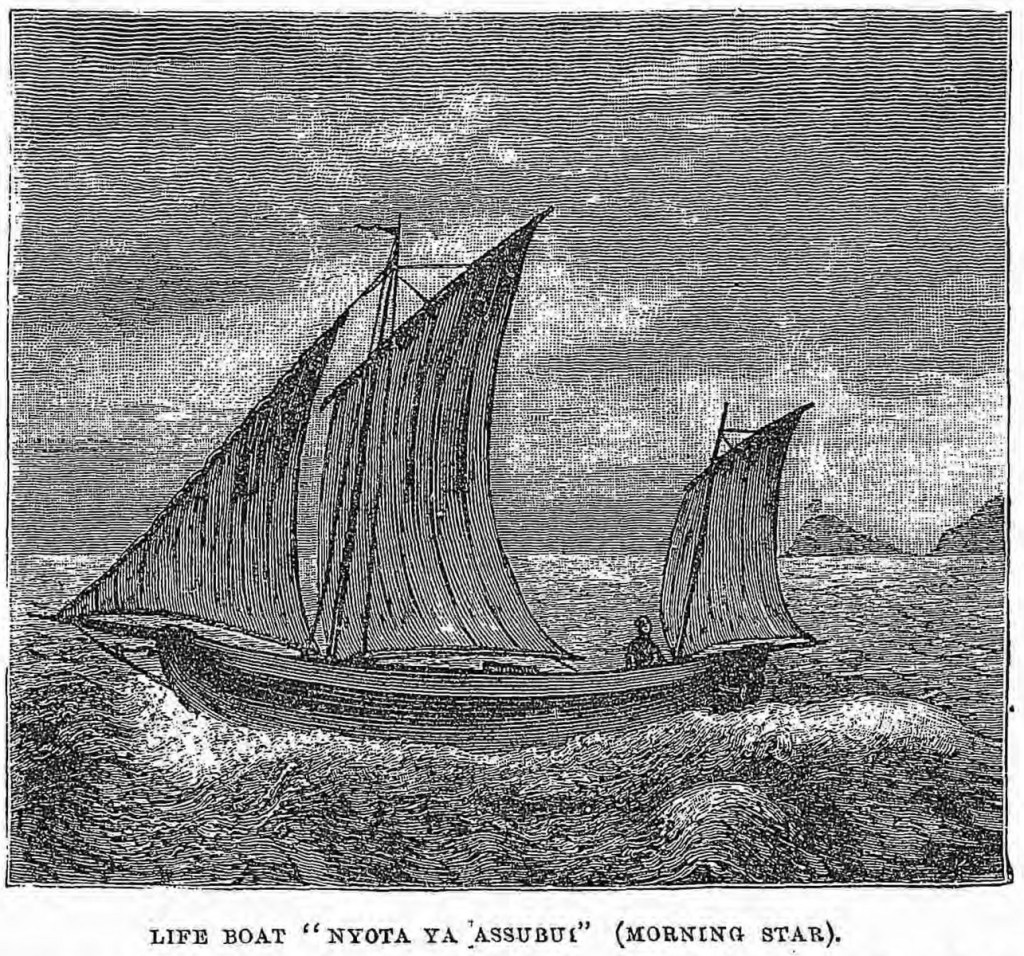

She was a remarkable woman. This was of course 1881 in Victorian-era England, and if you were a vibrant, outgoing woman and dedicated Christian and wanted to see the world and spread the message of Jesus you were pretty much out of luck, unless you got yourself married to a missionary (I am ignoring the moral quandary of missionary work here). As she says in her writing, she married Edward not in spite of his missionary work but as an enthusiastic partner of it. And so, eleven months after they were married she gave birth to their son Jack (February 1882), and five months after that (July 1882) she found boarded along with her husband and infant son the steamer Quetta bound for Zanzibar.

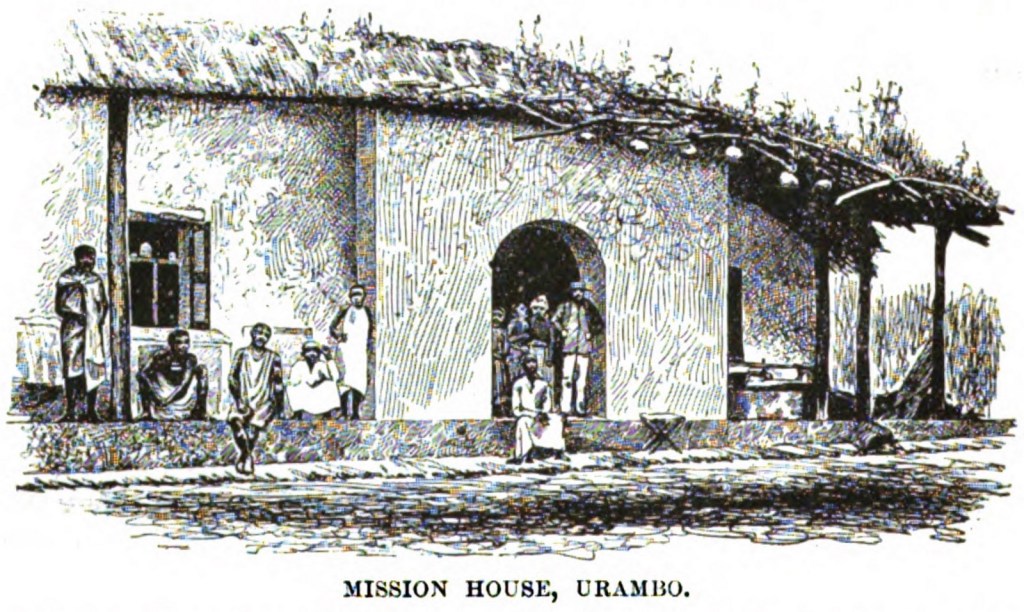

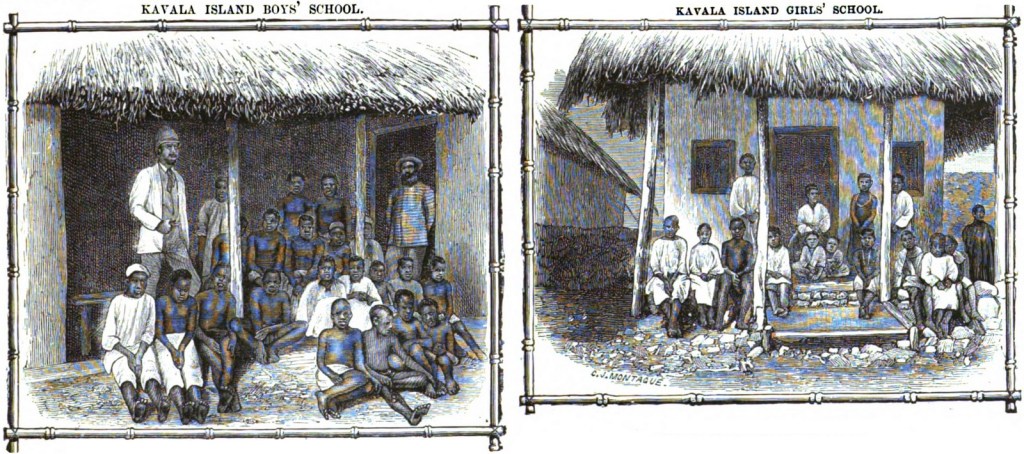

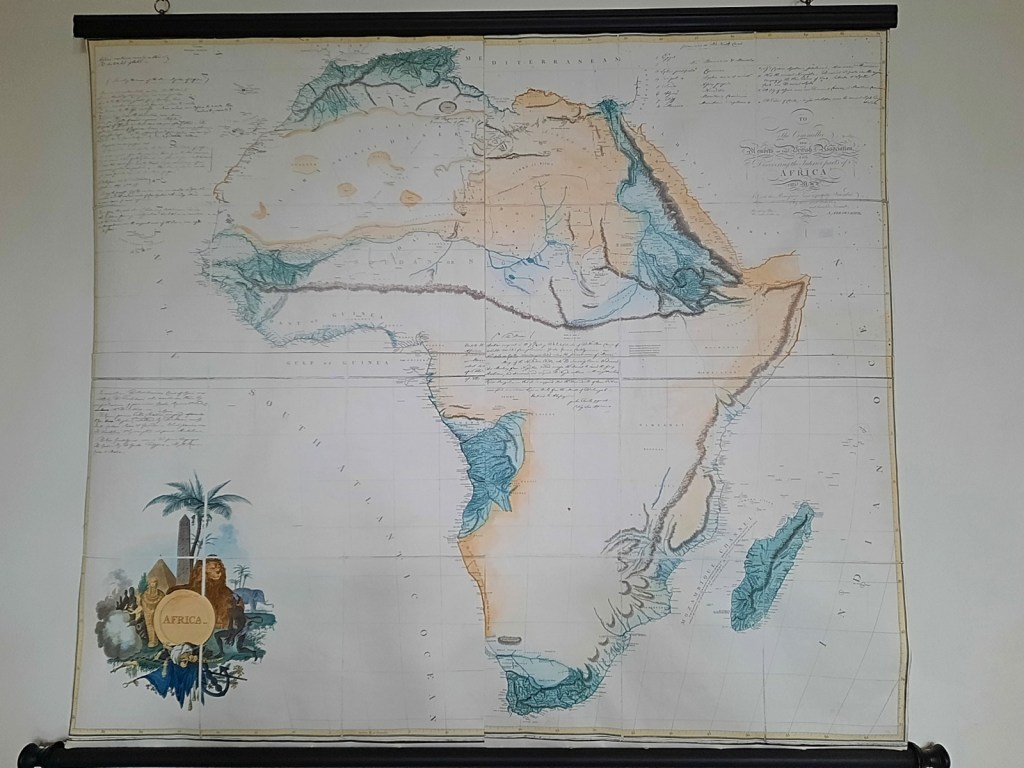

The act of getting from England to Lake Tanganyika is the story that comprises her book, To Lake Tanganyika in a Bath Chair (a “bath chair” here is like a wheelchair). It was not easy! They started one overland caravan but had to turn back when Annie got sick. She returned to England and then the next time she tried to go to the Lake it was via Lake Malawi (then Nyasa). They had to turn back from that due to fighting along the route, and so they began once again on the overland route. The wheels of the bath chair were not very effective, so it was essentially converted to a palanquin, and it was on the shoulders of 16 porters (though only two at once) that she travelled to Lake Tanganyika, becoming the first European woman to do so. She also thus became the first woman to join the Central African mission and started their first school, a school for girls.

I very much recommend a read of Annie’s book. Unfortunately it is nearly impossible to find. Unlike her husband’s book it only received a single edition. However, thanks once again to the Yale Library, I was able to obtain a copy and spent two who days transcribing it for the benefit of the internet and the world. Please find it below. I think the book is very witty, and Edward claiming that they should just get a move on down the road is channeling the exact same energy my dad has whenever he is on a roadtrip. It is also a unique look into fairly early European travel into Africa from the perspective of someone who is not a militaristic white dude. (When the Chronicle reviewed her book in January 1887, they overall recommended it, but noted that the introduction and conclusion by “E.W.” “does not add much to the value of the book, and is disfigured by some glaring inaccuracies,” which is true, but also that “the portraits of Mrs. Hore and ‘Jack’ are not pleasing likenesses, which is whack and shows the value of certain kinds of people’s opinions.)

Once in place on Kavala Island, Annie threw herself into missionary work and excelled at it. It was a little slow going as first, as she and Jack were recovering from illness, but she soon started a school for girls, which in turn inspired Edward to finally start a school for boys. From Edward himself: “I may say I have worked from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., for months past, and it is certainly as master of works that I have gained [Chief] Kavala’s admiration; but the center and strength of our powerful influence doubtless lay in the arrival and presence of my wife and child, and its resulting details in Mrs. Hore’s girls’ school.”

The Hores returned to England from Central Africa for the last time in October 1888. When I read the Chronicle I am astonished that the missionaries would take their children into Central Africa, given the high mortality rate of missionaries there. But for the Hores, although their son Jack survived the rigors of caravan travel and spent his childhood on Kavala Island, it was upon their return to England that he fell ill and died in London in April of 1889. According to deceasedonline.com, he is buried in Camden (search “Hore” and “1889”).

In August of 1890, however, Annie gave birth to a daughter, Joan, and in 1894 the Hores moved to Australia where Edward continued to work for the London Missionary Society for a time. Annie had relatives in Australia, and in his article Dr. Meyer notes that “[Edward] was dour, grey and humorless; a personality in sharp contrast to that of his wife Annie who, while a devout Christian, had a great sense of humor and an ebullient personality and who was loved and admired by all who knew her. When Edward and Annie Hore visited the Meyer [Annie’s cousins] family in Sydney, which they did frequently after 1890, Edward, with his difficult personality, was ‘tolerated’ for the sake of his wife, who was popular and always welcomed.” Dr. Meyer also notes that, in helping fundraise for the Society, Annie’s “contributions were extensive and greatly appreciated… Annie Hore conducted many meetings and gave informal talks, mainly to women’s groups.”

When Edward finally left the Society for good, they settled in Tasmania where they ran a small farm. This farm, again according to Dr. Meyer, was not successful for a long time, but eventually matured into a productive if modest estate and when they sold it provided sufficient funds for a final retirement. Annie and Edward were respected members of the community. After suffering a stroke, however, Edward died in 1912. Annie outlived him by four days short of ten years, with both buried in the Cornelian Bay Cemetery in Hobart, Tasmania. Her epitaph reads “Missionary.”

Notes on this transcription: I have made some effort to proofread this transcription. However, I have maintained several of the book’s typos while contributing some of my own, and which is which is an exercise for the reader. I have included the best scans I could of Annie’s portrait, Jack’s portrait, and the map of her route. The book includes a map of Lake Tanganyika which is the same map prepared by Captain Hore that can be found in a variety of places, including here. I have also tried to put the pdf together in a fairly pleasing way but there was only so far I was able to go.

You must be logged in to post a comment.